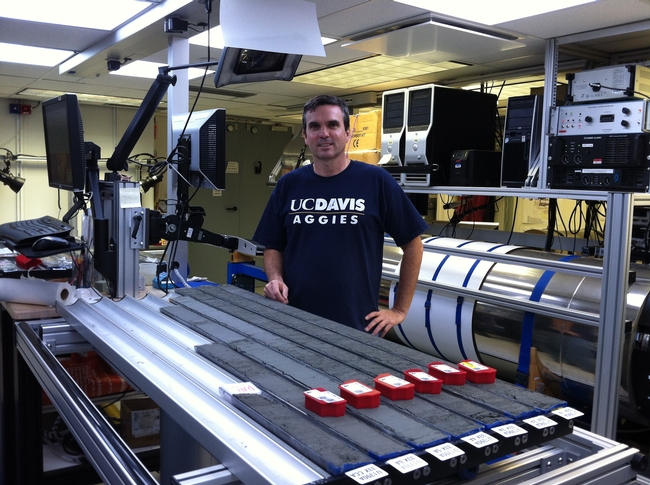

UC Davis geophysicist Gary Acton is one of 34 international scientists that set sail from the Azores Islands on Nov. 17 aboard the drilling vessel JOIDES Resolution. They finished their Mediterranean voyage on Jan. 17, docking in Lisbon, Portugal.

“The climate change recovered at one of the drill sites will be dedicated to providing the most complete marine record of climate change over the past 2 million years of Earth’s history,” said Acton.

The vessel is run by the Integrated Ocean Drilling Program and has the unique ability to core into the deepest reaches of the ocean. The IODP Expedition 339 targeted thick sediment drifts that accumulated from warm, salty water—called Mediterranean Outflow Water—flowing from the Mediterranean through the Strait of Gibraltar. The researchers drilled, sampled and analyzed the sediment to understand the influence that the MOW water mass has on climate, sea level change and the environment.

“A fascinating aspect of these sediments is their ability to record subtle changes in environmental conditions through measurable changes,” said Acton.

Made heavy by its high salt content, the MOW’s warm waters plunge over 3,000 feet—a drop greater than that of Angel Falls, the world’s highest waterfall—into the Atlantic Ocean. It scours the rocky seafloor, coursing along the margins of Spain and Portugal. Passing Scotland and heading toward Norway, the MOW becomes part of the global conveyor belt that overturns the oceans and circulates water and heat around the globe. Along its journey, sand, silt, clay and microorganisms are deposited along the continental margin as thousands of layers of mud, eventually building into sediment drifts. Each layer contains information about Earth’s history.

“My goal is to reconstruct centennial-scale changes in climate and in Earth’s magnetic field for a time period spanning the past 400,000 years,” said Acton. “Only thick, rapidly deposited sedimentary units like those we are coring provide that ability. They are virtual prehistoric observatories.”

During the expedition, the scientists sailed more than 1,200 nautical miles, drilled 19 holes in 7 different locations, and collected 681 sediment cores—equal to about three miles of mud and sand. Now that the researchers have returned to their homes, they will continue to collaborate as they sift through the data.

“Part of the true value of participating on an expedition like this is the incredible amount of science that can be completed, particularly when scientists with a variety of expertise are confined to a 471-foot-long ship and asked to work 12-hour shifts for two months,” said Acton. “That may seem an odd thing to do over the holidays, but we were all thrilled to be a part of this expedition and to have the chance to continue to work together following the cruise.”